John Kendrick (1922-2013)

John Kendrick spent 20 years filming and recording wildlife throughout New Zealand while working for the Wildlife Service.

He began donating recordings to Radio New Zealand in the late 1960s when he became irritated with what he described as "the monotonous squawk" heard regularly on the airwaves and decided to supply more pleasing birdcalls.

"The director of national programmes of the day was a little bit hesitant, but I felt it was a good idea to share these recordings with the general public of New Zealand.

"So I said, 'Well, give it a go'. They put them on and they got a good reaction from the public apparently and it's just kept on going all these years."

His favourite call was the kokako "because of it's sort of mystic, wonderful echoing organ-like notes."

In 2010, Mr Kendrick was awarded the Queen's Service Medal for services to wildlife.

Memoirs Of A Sound Recordist

John Kendrick shares some memories of his long association with the late Geoff Moon, New Zealand’s most renowned bird photographer, whose images illustrate New Zealand Bird Calls by Lynnette Moon, Geoff Moon, John Kendrick and Karen Baird, published by New Holland.

This extract has been made available with kind permission of New Holland publishers.

"My first trip with Geoff was in 1958. ‘I’ll show you some fairy terns and New Zealand dotterels at Pakiri Beach,’ he said, so off we went in his Land Rover with another friend, John Warham. I shot some movie footage on my old Canon 8 mm and Geoff took photos.

I first met Geoff through mutual Ornithological Society friends Ross and Hetty McKenzie, having joined the society in 1955. At the time, I was running my own radio and electronics business, and Ross was keen for me to make sound recordings of his local kokako population in the Hunuas near Clevedon. In those days I had a fairly rough-and-ready valve tape recorder. We staked out a plot below an old miro tree frequented by the birds, and made the first ever sound recordings of a kokako. From then on I was hooked! My next unit I built myself as it was hard to get a decent, portable and affordable recorder in those days. It ran off car batteries, requiring an inverter, which made it less than portable. Some years later, the Wildlife Service purchased the Nagra 3, a Swiss-built professional machine, which transformed my recording quality from then on.

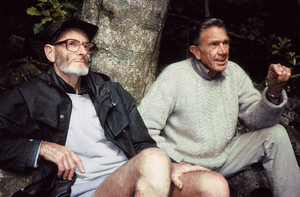

John (left) and Geoff on Kapiti Island during the filming of the Natural History production Sanctuary, part of the Wild South series, in 1988. Image courtesy of Lynette Moon/New Holland.

Geoff’s skills as a veterinarian were often put to use on wild birds. I once arrived at his house to find he had patched up a morepork with a damaged wing. I believe he let it go outside their bach at Scandretts Bay, which is where he got some of his first photos of moreporks. Keenly interested in bird behaviour, he always took opportunities to help birds and learn more about them.

Quite early in our association Geoff proposed a three-week safari to photograph a recent Australian immigrant, the black-fronted dotterel, which was now to be found in the riverbeds of the Hawke’s Bay and central North Island. Geoff’s friend Clive Wickens owned a magnificent Ford station-wagon. After much planning, we set off south in the spring of 1961, the Ford crammed to the gunwales with kit. En route, we visited the Kaimanawas, where we tramped for two hours up the Waipakihi River and found a great many riflemen – and a rifleman nest. Geoff was keen to go back to the car for a hide, adding four hours to our walk, but I assured him we would find another rifleman’s nest on our three-week tour. (Sadly, we never did, and Geoff would periodically remind me of this great loss.) Anyway, off to the Hawke’s Bay, where we walked up and down the Tukituki, Ngaruroro and Tutaekuri rivers. We eventually found nests of the black-fronted dotterel and set up hides.

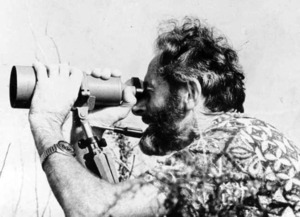

John watching birds. Image courtesy of Karen Baird/New Holland.

To be good at photographing from hides you have to know birds and their behaviour, and Geoff generously shared all his secrets and skills. When I joined the Wildlife Service, these skills assisted me a great deal. He taught me, for instance, how to set up a hide without disturbing the birds. (As he was always careful to point out, the birds’ welfare took priority over any photography.) The trick was to move it bit by bit into position, so that the bird gradually got used to it.

After this, we went on many an expedition together. There were voyages on the launch of Gordon McKenzie, a Clevedon friend, to photograph spotted shags diving for fish at the northern cliffs of Waiheke Island, and up through the islands off the Coromandel coast, taking in the gannet colony at Happy Jack Island/Motukahaua. On another trip, Geoff and I went with Len Doel to the South Island for the cirl buntings. It was a little early for nesting, but I did get the first recordings of cirl buntings and Geoff some pictures.

I had sold my business in 1963 and applied for a position as an audio-visual officer with the Wildlife Service, transferring to Wellington in 1964. Luckily, Geoff was appointed to the Veterinary Council, whose meetings were held in Wellington, which meant he could visit me at my home in York Bay. There was always an opportunity to do something ornithological when he came down.

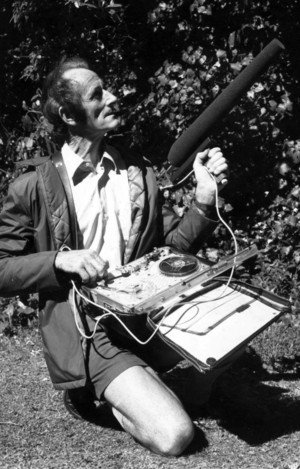

John in the field in the 1970s. Image courtesy of Karen Baird/New Holland.

In January 1964, the Wildlife Service felt we knew enough about saddlebacks on Hen Island, so they sent us out to catch thirty birds and move them to Middle Chicken. Geoff was invited to come along to photograph and provide veterinary advice. I had already obtained a number of recordings of the birds in August and September 1963, but I took the recording gear, as I realised it could make all the difference in capturing the birds.

Don Merton brought the first mist nets, which we set up in suitable places, then I planted my speakers one each side of the mist net. Using my sound recordings, and a rather battered-looking saddleback decoy – a new technique in those days – we lured the birds into the net, switching the sound from one speaker to the other to draw them in. Every morning, each of us gathered half a jar of insects and grubs to feed the birds. Once we had collected our thirty, the birds were crated, the Navy picked us up and we took them to Middle Chicken – the first successful release of saddlebacks anywhere.

Later, we were both involved in the early kakapo searches at Esperance Valley in Fiordland in 1973, working with Don Merton and others. Good-quality recordings were essential to enable us to capture the birds. Geoff’s role was critical, too: to look after the welfare of captive birds and see them safely to their new home of Maud Island. (One of them, which we had christened Richard Henry after an early naturalist, survived until 2010.)

After I had retired from the Wildlife Service in 1982, we visited Kapiti together. We had been watching kaka, but it’s hard to find the nests of these secretive birds. I eventually saw one acting suspiciously, and sure enough, we found a nest inside a tree trunk with several different holes. We set up a hide and spent many hours happily observing and recording their behaviour. There was a return to Kapiti in 1988, when Mike Hacking, a director for the Natural History Unit, made a film about my sound recording work and Geoff’s photography and set it on the island. The documentary, titled Sanctuary, was part of the Wild South series and included some of my own film material, as well as some great shots of Geoff’s hide work.

Geoff and I continued to do many birding excursions in our retirement until ill health prevented him from getting out in the field. I remember Geoff as a generous mentor, whose deep fund of knowledge was shared with many people, and as a skilful photographer and wonderful friend."

John Kendrick at the launch of New Zealand Bird Calls (book and CD) by Lynnette Moon, Geoff Moon, Karen Baird and John Kendrick. Image courtesy of New Holland.